Australia’s Baptism of Blood?

John Collard

George Lambert’s portrait of CEW Bean, 1935

The official Australian War Historian CEW Bean is credited with mythologising the experiences and ignominious withdrawal of Anzac troops from the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915 as a “baptism of blood”, the new nation’s transition from colonial adolescence to international maturity. He accompanied the Australian Military Forces to both Gallipoli and the Western Front from May 1915. Upon his return to Australia, he was based at Tuggeranong Homestead near Canberra from 1919 to 1925. He wrote six volumes of the twelve volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 (Bean, 1946), and was instrumental in the establishment of the Australian War Memorial and the creation and popularisation of the Anzac Legend.

Bean drew heavily on movements of literary nationalism in the two decades that preceded Federation in 1901. The heroic mateship celebrated by Banjo Patterson was a strong influence upon his portrayal of Australians at war. However, he overlooked the fact that the period 1914-1918 was not actually the initiation of Australians into war. That had accompanied the displacement of the indigenous inhabitants in frontier wars across the continent. Contemporary historians consider the period of “frontier wars” to extend from 1788–1934. Some would argue that issues such as “black deaths in custody” are a manifestation of this warfare to the current day.

The sudden arrival and occupation of British settlers in Australia led to competition for resources with Aboriginal inhabitants. However, conflict was usually between groups of settlers and individual tribes rather than systematic warfare. There were occasions when British soldiers became involved, and mounted police units recruited Aborigines to pursue tribes who resisted white settlement. The violence tended to be localised, because the structure of Aboriginal tribes prevented them from organising confederations capable of sustained resistance. (Haw & Munro, 2010)

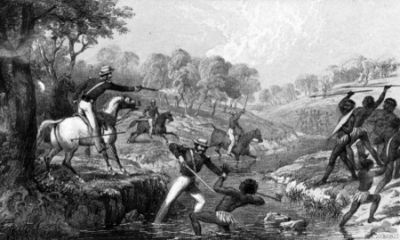

The result was not a single war, but a series of violent engagements and massacres across the continent. Among the most famous were the Black Wars in Tasmania between 1828 and 1832, which sought to drive most of the island's native inhabitants onto a number of isolated peninsulas, the Battle of Pinjarra (Western Australia, 1834) and the Myall Creek Massacre (New South Wales, 1838).

Mounted police attacking Aborigines during the Slaughterhouse Creek Massacre, 1838

In Victoria and southern parts of South Australia, the majority of the violence occurred during the 1830s and 1840s as settlement expanded. It is estimated that over 20,000 Aborigines perished in “frontier violence” between 1788 and 1930. However, the impact of diseases introduced by white settlement was more devastating.

Much of southern and central Victoria was occupied by the Kulin People, in five distinct but strongly related communities. The two tribes in the Bendigo region in central Victoria were the Dja Dja Warrung in the Loddon Catchment to the north and west, and the Duang Warrung (also referred to as the Taungurung in many accounts) in the Campaspe Catchment. The people were organised into clans of about 100 each. It is estimated the combined tribes numbered between 2,000 and 3,000 when white settlement began in the region in the 1830s (Haw & Munro, 2010). The Dja Dja Warrung were called the Loddon River Tribe by white settlers. They were initially viewed as a “strong, physically well-developed people” (Cusack, 2002). They had complex trading networks.

There is evidence that smallpox epidemics that spread from Sydney in 1788 swept through the region in 1789 and 1825, and decimated the indigenous population at the time. Major Mitchell commented on the scars on surviving adults in the Swan Hill area in 1836, and it is estimated that half to two thirds of the local tribes were eliminated by smallpox. From the late 1830s European contact introduced consumption, venereal disease, the common cold, bronchitis, influenza, chicken pox, measles and scarlet fever. Venereal diseases (syphilis and gonorrhoea) reached epidemic proportions and 90% of Dja Dja Warrung women were thought to be suffering from syphilis by late 1841. This also had the effect of rendering them infertile and caused a plummeting birth rate (Haw & Munro, 2010). Those most dramatically affected were the groups who had most contact with European settlers.

White settlement followed promptly in the years up to 1842. Captain Hutton, who had been a lieutenant in The Bengal Army, established The Campaspe Plains Station in 1838 in the area now known as Axedale. Such developments severely disrupted traditional sources of food and medicines, introduced diseases and caused violent conflict with the white settlers (Cusack, 2002). In 1885 Kimberly cited the observations of JJ Pascoe, an earlier observer of the settlement process:

“One day the black man was monarch of all the wilderness. A few days later his domain was invaded by the white man…The invaders took possession of the land because it was goodly and the black savages melted away before their very presence and were dispossessed in every direction” (Kimberly, 1895)

Hutton squatted on 114,000 acres in 1838, and the following year two of his shepherds were killed after conflict with the Dja Dja Warrung, who had speared a sheep. The next day he organised a vigilante squad of white settlers to pursue the offenders. Nineteen of the Dja Dja Warrung were shot as they fled, and the following day another six met the same fate. Hutton sold his land to other settlers in in 1840 for £10,000 (Cusack, 2002). Crippling droughts and depression in succeeding years saw portions of this property sold to others.

This frontier history is of particular interest to my own extended family. In the 1850s, the land was further divided and sold to Irish immigrants. My great grandfather was one of these purchasers and we still own considerable acreage there to this day. In this respect, my family, like many others in Australia, became beneficiaries of the frontier wars, for we continue to own farmland where Captain Hutton initiated a massacre of local Aborigines.

By December 1852 the population of Dja Dja Warrung was estimated at 142 people, whereas they had numbered between one and two thousand just 15 years previously. In 1864 when they were resettled to Coranderrk near Healesville there were only 31 adults and seven children left (Haw & Munro, 2010). In the past two years two elders from the tribe have returned to the area. However, in the intervening decades tales about shadowy dark figures appearing around the local cemetery on misty nights have become entrenched in local folklore. The Campaspe Creek Massacre therefore provides a clear illustration of how the frontier wars continue to feature in Australian history.

Other initiations into war occurred in the second half of the Nineteenth Century as colonial regiments were raised to support Britain in imperial disputes. In 1861, the Victorian ship HMCSS Victoria was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. In 1863 further troops were lured to assist in the invasion of the Waikato Province by the offer of free land settlements. In 1885 the New South Wales government sent an infantry battalion and an artillery battery to support British efforts to repel rebellion in Sudan. Conflict between Britain and Afrikaners in South Africa in the 1890s led to the Second Boer War in 1899. Each of the six Australian colonial governments sent separate contingents to serve with British formations. My family became involved in this when a cousin from Sydney, Gus Slattery, joined the NSW Lancers.

We have a number of letters that Gus sent home to his family and local newspapers while he was away. These clearly indicate that his preparation for and subsequent “baptism of blood” was completed well before World War 1. The volunteers went to England at their own expense, in the hope that they would be accepted for service in the war. They were welcomed by huge crowds as they travelled through the streets of London and were feted by some of the country’s most senior political figures. The former Prime Minister, Lord Roseberry, gave a banquet for the 70 Lancers at his Buckinghamshire palace. Gus wrote:

“I cannot explain it; the grandeur and magnificence of it would blind you … I never saw such a table in my life. The dinner service was of gold too. First of all we had soup, then followed in quick succession fish, oysters, roast beef, ham and chicken, ducks and ox tongue. For dessert there were jellies and ices of all descriptions, and the drinkables were numerous, including champagne, champagne cup, claret cup, claret, port, sherry, ginger beer, lemonade and soda water, so you can see for yourself what a grand time we had. The fruit was beautiful, especially the hot-house grapes… The next performance was cigars and cigarettes, brought round by the flunkies, and they even struck the matches and held them up.” (The Sydney Stock and Station Journal, 13 October 1899)

He also mentioned that they were to be entertained the next week by Lord Carrington, a former governor of New South Wales. Their farewell from London was another parade through the crowded streets, an address by the Lord Mayor and then a farewell at the station by Lord Carrington and Lord Hampden, another former governor of New South Wales.

Life in South Africa was rather different: long marches, battles, tight rations, temperatures of 105° F and the ravages of war, but at all times Gus exhibited a sense of pride in what he was doing for the “mother country.” On 30/1/1900 the Evening News in Sydney published a letter from a comrade of Gus Slattery which provided details of their living conditions. Walter Ellis reported that:

“Our bill of fare is simplicity itself. Breakfast, a pint of coffee. Dinner, half a pound of meat. Tea, a pint of tea and half a loaf of bread. When no bread is attainable, three dozen biscuits a man.”

Gus’ first post refers to “giving the Boers a jolly good hiding” in typical British military rhetoric. On other occasions it was more realistic. In his account of the Relief of Kimberley and the capture of Afrikaner troops he wrote:

“We had heavy rains at the camp and having no tents we were soaked through nightly. The wonder is that we did not all fall victims to colds … on half rations too, having, of course, to share with our guests.” (The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 5 May 1900).

He was also obviously moved by much of the suffering and devastation that he saw. Amidst his rejoicing in the capture of Kimberley he lamented the terrible state of “the poor starved looking creatures, especially the women and children, who were forced to live in holes in the ground (The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 5 May 1900). He also observed that:

“It was a sickening sight. In the trenches were dead and wounded Boers, and horses, cattle and mules lying dead all over the place, the stench of which was something awful” (Hawkesbury Advocate, 27 April, 1900)

New South Wales Lancers in South Africa

However, by the end he was satisfied that “… the NSW Lancers will go home covered in glory.” (Hawkesbury Advocate, 27/4/1900). The horrors of war he witnessed were short lived in his memory for he was among the first to volunteer when World War 1 was declared in 1914.

After the defeat of the Afrikaner republics, the Boers formed commando units and conducted a form of guerrilla warfare to disrupt British troop movements and lines of supply. This new phase led to further recruiting in the Australian colonies and the raising of the Bushmen's Contingents, with these soldiers usually being volunteers with horse-riding and shooting skills but little military experience. After Federation in 1901, eight Australian Commonwealth Horse battalions of the newly created Australian Army were also sent to South Africa, although they saw little fighting before the war ended. Such units included the Bushveldt Carbineers, who gained notoriety as the unit in which Harry "Breaker" Morant and Peter Handcock served before their British Court Martial and execution for war crimes.

A total of 16,175 Australians served in South Africa: 251 were killed in action; 267 died of disease; and 43 went missing in action. A further 735 were wounded. Six Australians were awarded the Victoria Cross.

The dawning of the next century was accompanied by the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. This was to engage Australians in their first international, as opposed to imperial, conflict. A number of western nations, including many European powers, the United States and Japan, sent forces as part of the China Field Force to protect their interests. In June, the British government sought permission from the Australian colonies to dispatch ships from the Australian Squadron to China. The colonies also offered to assist further, but as most of their troops were still engaged in South Africa, they had to rely on naval forces for manpower. The force dispatched was a modest one, with Britain accepting 200 men from Victoria, 260 from New South Wales and the South Australian ship HMCS Protector. The contingents from New South Wales and Victoria sailed for China on 8 August 1900. They left China in March 1901, having played only a minor role in a few offensives and punitive expeditions and in the restoration of civil order. Six Australians died from sickness and injury, but none were killed as a result of enemy action.

The foregoing account indicates that treating Australia’s involvement in World War 1 as “a baptism of blood” was both inaccurate and a radical overstatement. It is more accurate to regard it as a continuation of responses to British imperial interests. The frontier wars were a feature of white occupation of the continent and the indigenous inhabitants were the major victims. The Campaspe Creek Massacre indicates that there were also white casualties in such conflicts. The baptisms in overseas conflicts were a response to imperial demands and sentiments. Bean’s representation of our nation’s involvement in World War 1 is inaccurate and our Anzac tradition is based on faulty historical thinking.

References

The preceding account draws upon research undertaken for an extended family history County Clare Axedale & Beyond; An Irish Clan Downunder (Collard & O'Grady, 2015). It draws upon the following references: The Anzac Book (Bean, 1916), The Official History of Australia in the War 1914-1918 (Bean, 1946), Bendigo A History (Cusack, 2002), Footsteps Across The Loddon Plains: A Short History (Haw & Munro, 2010) and Bendigo and vicinity (Kimberly, 1895).