This poem was written after reading John S Croucher (2014), The Kid from Norfolk Island – The Story of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1942: Ten Weeks that Forged our Nation

A captain (then retired, now passed)

told me of his Kokoda trials in ’42.

He’d seen it through as a pacifist.

He spoke of his father’s words on world war two:

“Don’t rush to enlist, son.

They didn’t do right by us in the last one.”

He soldiered with my uncle on Kokoda.

He led them there with one firm aim –

to keep his men alive. I’m thankful, and I wonder

how these two men, the captain and uncle Bill,

both whimsical and gentle souls,

managed all they found up that track?

Sixty four years I’ve struggled

to know my dad (now gone 16 years).

Silent on his past, focused on his work,

as builder and breadwinner –

the gulf between youth and man filled

for him on Singapore in ’42.

Then I found Alf, in a book;

this unplanned third source helped triangulate

proof of ’42 – not Gallipoli – as our

nation’s crucible of shock and awe;

to know how that sharp scalene angle of war

raids had strafed pacific fleets and views.

In ten short weeks our antipodes

upended, and new views formed from

Pearl Harbour, Singapore, Darwin:

our remote felicity attacked, point-blank.

In February ’42: two raids, four carriers –

243 killed in Darwin, on our soil.

For dad and Alf, the captain and uncle Bill,

this was their generation’s “final straw”

that broke the back of their resistance

to being lured to fight others’ wars.

For many, only then,

were they ready to enlist.

Historical Footnote

After the attacks on Pearl Harbour and Singapore, Australia declared war on Japan. We did not wait for a British declaration. In early 1942, as Japan pushed further south and invaded New Guinea, Prime Minister Curtin requested our troops be returned to (defend) Australia. Churchill wanted them sent to Burma. Curtin’s resistance won out, “the mouse that roared.” Australia adopted the Statute of Westminster in 1943 – no longer the colonial dominion. The British Government would no longer make decisions for Australia. So 1942 is our true national crucible – the situation of severe trial, that led to the creation of a new footing for our nation. It is, of course, a whole other question whether our ditching of the colonial yoke to hook up with post-WW2 US alliance, that new friendship forged through mutual trust, has not cost us more independence in the long run.

Appendix

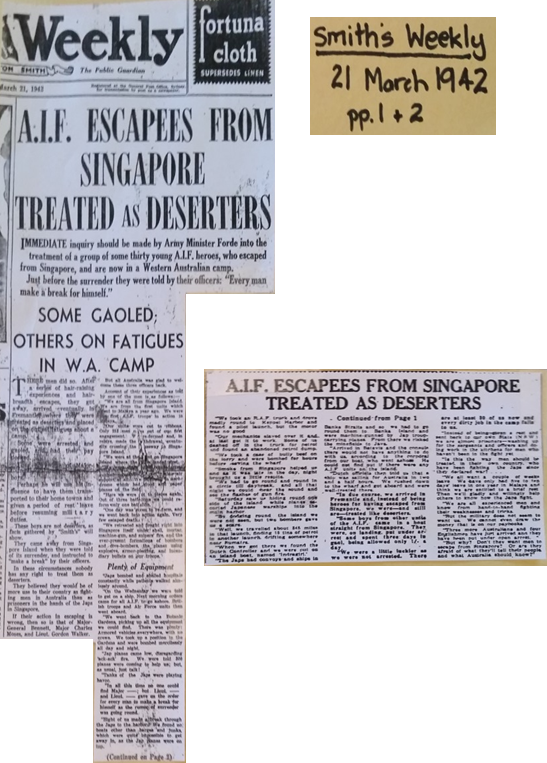

The following 1942 Smith’s Weekly article was provided for inclusion in Peace Works! publication from the private papers of Irving Goodfellow, one of the AIF escapees from Singapore. (It is not available on Trove.):

“A.I.F. Escapees from Singapore Treated as Deserters”, Smith’s Weekly, 21 March 1942, pages 1 and 2

Immediate inquiry should be made by Army Minister Forde into the treatment of a group of some thirty young A.I.F. heroes, who escaped from Singapore, and are now in a West Australian camp.

Just before the surrender they were told by their officers: “Every man make a break for himself.”

Some Gaoled; Others on Fatigues in W.A. Camp

These men did so. After a series of hair-raising experiences and hair-breadth escapes, they got away, arrived eventually in Fremantle, where they were treated as deserters and placed on the dirtiest fatigues about a camp.

Some were arrested, and gaoled, and had their pay docked.

They are some of Major-General Gordon Bennett’s boys.

Perhaps he will use his influence to have them transported to their home towns and given a period of rest leave before resuming military duties.

These boys are not deserters, as facts gathered by “Smith’s” will show.

They came away from Singapore Island when they were told of its surrender, and instructed to “make a break” by their officers.

In these circumstances nobody has any right to treat them as deserters.

They believed they would be of more use to their country as fighting men in Australia than as prisoners in the hands of the Japs in Singapore.

If their action in escaping is wrong, then so is that of Major-General Bennett, Major Charles Moses, and Lieut. Gordon Walker.

But all Australia was glad to welcome these three officers back.

Account of their experiences as told by one of the men is as follows:-

“We are all from Singapore Island. We are from the first units which went to Malaya a year ago. We were the first A.I.F. troops in action in Malaya.

“Our units were cut to ribbons. Only 253 men came out of our first engagement. We re-formed and, in relays, made the withdrawal, eventually crossing the causeway to Singapore Island.

“We were at the point on Singapore Island where the Japs landed first. We were shelled and bombed continuously for 18 hours and machine-gunned constantly and had no air support at all. We defended an aerodrome which had wood and paper planes on the field.

“Here we were cut to pieces again. Out of three battalions we could re-form only one battalion.

“One day was given to re-form, and we went back into action again. Very few escaped death.

“We retreated and fought right into Singapore itself under shell, mortar, machine-gun, and snipers’ fire, and the ever-present formations of bombers and dive-bombers, the planes using explosives, armor-piercing, and incendiary bullets on our troops.

Plenty of Equipment

“Japs bombed and shelled hospitals constantly while patients walked aimlessly around.

“On the Wednesday we were told to get on a ship. Next morning orders came for all A.I.F. to go ashore. British troops and Air Force units then went aboard.

“We went back to the Botanic Gardens, picking up all the equipment we could find. There was plenty: Armored vehicles everywhere, with no crews. We took up a position in the Gardens and were bombed mercilessly all day and night.

“Jap planes came low, disregarding ‘ack-ack’ fire. We were told 300 planes were coming to help us; but, as usual, just talk!

“Tanks of the Japs were playing havoc.

“In all this time no one could find Major ___; but Lieut. ____ and Lieut. _____ gave us the order for every man to make a break for himself as the rumor of surrender was going round.

“Eight of us made a break through the Japs to the harbor. We found no boats other than barges and junks, which were quite impossible to get away in, as the Jap planes were on top.

Continued from Page 1

“We took an R.A.F. truck and drove madly round to Keppel Harbor and found a pilot launch, but the motor was no good.

“Our mechanics slaved over it and at last got it to work. Some of us dashed off in the truck for petrol and found an abandoned petrol dump.

“We took a case of bully beef on the lorry and were bombed for hours before leaving the wharf.

“Smoke from Singapore helped us and as it was late in the day, night brought us a little respite.

“We had to go round and round in a circle till daybreak, and all that night we could hear the sound and see the flashes of gun fire.

“Saturday saw us hiding round one side of the Island while planes escorted Japanese warships into the main harbor.

“By dodging round the Island we were not seen, but two bombers gave us a scare.

“Well we travelled about 345 miles in that launch, finding 15 tins of petrol in another launch, drifting somewhere near Sumatra.

“When we got there we found the Dutch Controller and we were put on an island boat, named ‘Indragirl.’

“The Japs had convoys and ships in Banks Straits and so we had to go round them to Banks Island and were machine-gunned by Jap troop-carrying planes. From there we risked the minefields to Java.

“Arrived in Batavia and the consuls there would not have anything to do with us, according to the corporal from our boat, who went ashore. He could not find out if there were any A.I.F. units on the Island.

“Dutch officials then told us that a ship was sailing for Australia in two and a half hours. We rushed down to the wharf and got aboard and were well-treated there.

“In due course, we arrived in Fremantle and, instead of being heroes for having escaped from Singapore, we were – and still are – treated like deserters.

“Some boys from other units of the A.I.F. came in a boat straight from Singapore. They were, on landing, put under arrest and spent three days in gaol, being allowed only 1/- [one shilling] a day.

“We were a little luckier as we were not arrested. There are at least 30 of us now and every dirty job in the camp falls on us.

“Instead of being given a rest and sent back to our own State [N.S.W.] we are almost prisoners – washing up for the sergeants and officers and doing work in the kitchens for men who haven’t been in the fight yet . . .

“Is this the way men should be treated in their own country, who have been fighting the Japs since they declared war? . . .

“We all want a couple of weeks leave. We have only had five to ten days’ leave in one year in Malaya and think we are entitled to a brief rest. Then we’ll gladly and willingly help others to know how the Japs fight.

“We are all experienced men and know from hand-to-hand fighting their weaknesses and tricks.

“But the military does not seem to want us. We cannot even draw the money that is in our paybooks.

“Three more Australians and four Englishmen have just arrived and they have been put under open arrest.

“But why? Don’t they want men to escape from Singapore? Or are they afraid of what they’ll tell their people and what Australia should know?