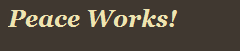

I went into camp at Liverpool along with many others and made friends with a couple of boys from towns not far from my own. Harold Andrews from Wauchope and Norm Way from Beechwood.

We drew three blankets each from the Q.M. Store and then filed into a large hut. We made our beds down on the floor side by side with one blanket under and the other two over us. It was our first night in the army and a night never to be forgotten. It was winter and the night was cold and the language hot. We had no sleep that night. I had heard bullock drivers stuck in a creek with a load of timber on, but they were not in the same race. I hadn’t heard anything to compare with it.

Next day we commenced our training and all went well for a week, then I developed Rheumatic Fever and was ill in the camp hospital for two weeks. Discharged from hospital I was given seven days leave and caught the train north for home at 8.00 a.m. the next morning. I left the train at Mount George and walked home, a little more than a mile. Feeling very ill I went to bed as soon as I arrived home and stayed there for six weeks with pneumonia and pleurisy.

I returned to camp again to go to Long Bay to the shoot. I didn’t need any training as I had grown up with a rifle in my hands. From 600 yards I got the “possible” for the day, only one other soldier got it out of the three hundred.

One week later, on the 5th October, we left Woolloomooloo, Sydney, aboard the Themistocles, to serve in the Middle East. Seventeen hundred men left Sydney on this ship and we picked up a further fifteen hundred at Fremantle in Western Australia

We arrived at Port Suez about five weeks later and were taken by train to a little town called Heliopolis, near Cairo. By this time Harold Andrews, Norm Way and myself had become good friends. When we could we would go to Cairo at the weekends just to visit the gardens where we were able to sit on the grass lawns and really enjoy it. There was no grass in Egypt other than the grass lawns in Cairo.

We went to see the rippling stream, where Jesus Christ drank water. I also drank water from the stream, and close by is the apple tree where the Blessed Virgin Mary sat in the shade of the tree. I pulled leaves off the tree and sent them home to my mother.

We went to see the Pyramids, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Inside, they consist of only two large rooms. One was just an empty chamber and you had to walk up a few steps to the other. It had a stone coffin built into the floor, but no lid was to be seen. Our guide said that there wasn't any record of it ever having had a lid. The guide told us that thousands of years before, a King or Queen had died and the body was lowered down from the very top of the pyramid into the stone coffin. We tried to climb one of the pyramids but the going was too hard and we had to give it away. We climbed half way up and then turned back. The pyramids are built of sandstone; these are still a mystery as no one knows where they came from or how they got them there. Each sandstone block is very large and it really does make you wonder. We also saw the Sphinx, which is close to the Pyramids.

We often engaged a local guide to show us places of interest and to tell us the stories connected with them. We saw many interesting places and heard many interesting stories there in Egypt. It was in Egypt that we did our training for a few months awaiting the evacuation of Gallipoli.

It was early in 1916 that we joined the lst Battalion. Harold and Norm were put into “C” company and I went into “D” company. We were posted to the Suez Canal and were to stay there as guard to the Suez. It was while we were there that we were to be visited by the Prince of Wales. I remember that day so well as the midday meal had to be deferred for some hours as he was delayed. Finally it was decided to serve the troops the long overdue and much looked forward to meal. So we all sat down and the meal was placed in our Dixies and the word came that the Prince of Wales had arrived and was ready to inspect the troops. That meant we had to leave the meal where it was and fall in. The boys, all hungry and tired by this time, sent up hoots and boos for the Prince instead of the expected cheers. Finally, when the inspection was over and we were dismissed, everyone made a dive for their tents to get back to their dixies holding the dinner of stew, but, as luck would have it, the fine sand that was always a curse had blown into the food spoiling it. Not one of us had dinner that day and we didn't get another meal until late that evening. It was a tough life.

From Egypt we went to France in March 1916. We landed at Marseilles on the 22nd March 1916. From there we boarded a train heading for the front line. After four days and nights on the train we arrived at a town call Steensworth and then we were sent straight up into the front line at a place called Sailly. We arrived there in the dark of night.

It was at Sailly we had our first experience of war, at a place nicknamed VC corner. It was as we were marching around the bend at VC corner that a German machine gun opened fire on us. We dived for cover, into ditches, behind trees or any other place that we could find. No one was killed but some were wounded. This part of the line was very quiet, but it didn’t remain that way after the Australians arrived there.

It soon became a very hot spot. We had sandbag trenches, but no “hopovers” or raids here. We stayed ten days in the line and ten days out for a rest. This went on for four months. After that we were marched to the Somme. It took four days with full packs on and we marched from early morning until late evening, with only a ten-minute spell in each hour. Many men could not make it and were forced to fall out and had to be picked up by horse drawn wagons.

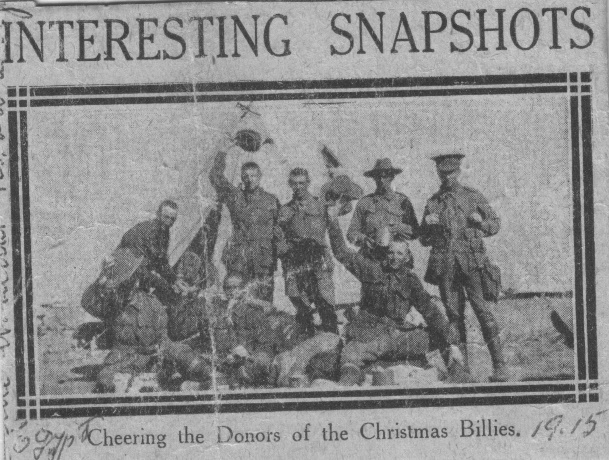

206. The Tower of Albert Cathedral

Past this the Australian troops marched on their way to Pozieres.

Near the buildings in the foreground were some which housed the Headquarters of the 1st, and afterwards of the 2nd, Australian Division during the greater part of the battle. Vol. III.

Aust. War Museum Official Photo. No. E167. Taken in January 1917.

Through this valley led the communications to Pozieres. At the date of this photograph (28th August, 1916), and for a month before and afterwards, this was one of the busiest thoroughfares of the world. At the top can be discerned the crossroad leading to “Casualty Corner” and Contalmaison; about half-a-mile beyond was Pozieres. Vol. III.

Aust. War Museum official Photo. No. EZ113.

It was four p.m. when we got back to our trench again and by dark that evening we were brought up to strength again for the big hop-over. Pozieres was ahead of us and held by the Germans at that time. My battalion was taken across “Sausage Valley” that night and stood in the front line of trenches waiting for the hop-over. (A hop-over is a bayonet charge).

At last the word was passed along the trench, the countdown was from five minutes to zero. Five minutes to go, was the message that was passed along, sixty seconds later, four minutes to go, etc., down to zero, then over the top. The artillery had already opened up as we went over the top with fixed bayonets.

The greatest battle that the world ever knew was on. The Germans knew that the Australians were coming to the Somme and they were ready for us. They put the Prussian guard in against us. They were Germany’s best-trained men, according to the German soldiers themselves. The Kaiser had told them that they were going to fight the Australians, the best soldiers in the world.

The world seemed to be on fire. It was unbelievable, only those who saw it could believe it.

It was said that four million shells an hour had been fired on our Front that night and just as many seemed to come from the Germans. Later we found German machine gunners chained to their guns. The cost of the battle on the Somme is impossible to estimate. The shock of the British losses on that frightful first day was extremely great, not only to those who survived, but also to Australia and Britain.

Among those who began to ask whether the top commanders knew what they were doing were members of the A.I.F. (Australian Imperial Forces). On the heights of Pozieres ridge and near by, Australians had lost 23,000 men in seven weeks and the names of Pozieres and Mauquet Farm are one of Australia's greatest battle fields.

Pozieres had been taken once by the Black Watch, a Scottish regiment, but they couldn't hold it. Pozieres was Germany’s strongest point, because it was the only area where the line had been pushed forward and there was a bend in the line there. This meant that German artillery could fire from three directions at once on the men dug in trying to defend the line, from the front, and from the right and left flanks.

Pozieres was taken by the Australians and held, after a long and bloody battle. The Germans counter attacked again and again with highly skilled soldiers, but failed. Here Australia proved to have the best soldiers in the world. This incredible barrage and counter barrage continued for three days and nights. The men of the lst division began to crack. They had lost about 5,300 men by this time. The village of Pozieres no longer existed by this time. There was simply no sign of it. Shellfire, and the powdered debris of the houses had been so churned up that it lay like a section of ash six feet deep. Men were buried dead or alive, only to be blown out and reburied again by German shells. Shell shock began to increase as men’s nerves gave way in the strain.

I was wounded here at Pozieres. Coming up to morning, I found my way back to the front line where we had started. By that time there were hundreds of others wounded and waiting to be taken back across “Sausage Valley.” The trenches were lined with men, some standing and others on stretchers. I said to one boy “Are you coming out Dick?”, he said “My arm is too bad to walk.” I said to him, “well it won't get better standing there” and walked on. It was daylight then and I had only gone about fifty yards when the Germans bombarded the trench where I stood talking to Dick. I saw men and stretchers blasted ten to twelve feet into the air. I walked on thinking to myself “you wouldn’t come with me Dick, you won’t come now.” Once again I had walked away from death. As I crossed “Sausage Valley” on my way out, the burying party was picking up what was left of men and stacking them in heaps ready to be buried. Our battalion was one thousand and forty men strong at midnight and after the battle of Pozieres there were only twenty men left to answer the roll call. The 2nd and 3rd battalion had about the same amount of men left, but the 4th battalion had fifty men left. So that should give you some idea. There were only a little over one hundred men left out of the lst brigade of four thousand men killed or wounded. I was taken out from there and sent to hospital. Later I was transferred to England and was in hospital in Newport, Wales.

I had been in hospital in Wales only three days when, to my relief and great surprise, Harold Andrews was admitted into the same ward as myself, a distance of only two beds away. He had been hit badly in the leg and he told me later that he had been picked up in a trench three days after the battle of Pozieres. It was good to see him.

I left hospital before Harold and was soon back in training camp. Within three months of my being wounded, I was again in France and joined my old unit. I remember seeing only three men in my company that I had known. All three of these men were at the landing of Gallipoli. Two of the men had been with the battalion all through the war and had not been wounded. They were Jimmy Coppen and Jimmy Rowe. The third man, Jimmy Allan, had been wounded once. They not only had the same Christian name in common, they shared other things equally as well. Two out of the three were in all major battles that the Australians took part in and had not been hit, but all three were killed later, in the Hindenburg Push, at the end of the war.

Jimmy Coppen and Jimmy Rowe had both been made sergeants. To see all three of these men suffering with shell shock and shattered nerves from the war strain while still soldiering on, was pitiful. It was a shame that they were sent into the line for that, the last battle of the war.

I have gone ahead of my story to explain about these gallant men and I will come to the Hindenberg battle later in my story. Returning to my unit, I went into the front line at Fricourt Farm. I missed the battle of Bullecourt, the second biggest battle for the Australians, but I was in many others. I stayed with my unit for many months, ten days in the line and ten days out for a rest. After our ten days rest as it was called, we went back into the line again and made another attack on the Germans, driving them out of the village called Albercourt and dug ourselves “in” on the outskirts of the village. At this time I was number one in a Lewis machine gun team of six men, including myself.

The Germans had made a stand, about 800 yards from where we had dug ourselves in. We could see them taking up position. A church was always the largest building in any small village in France and we dug our outpost in shoulder deep, 30 to 40 feet from this large brick church. We watched the Germans bring their big gun up on the railway and pointed it in our direction. We saw the gunfire and could hear the huge shell coming through the air. It hit the church and sent pieces of brick and rubble flying all over us and we couldn’t see for brick dust. This was about eleven a.m. one morning. Afterwards there was a big bombardment from the German artillery and our battalion was forced to retire, I did not know this, but we didn’t retire. That big gun fired one shell every three minutes from eleven o'clock in the morning until two o'clock the following morning. As each shell was fired we thought it would be the one to drop on us. This was very nerve shattering, our sergeant major came out and gave us the order to retire and told us that our battalion had withdrawn the night before. He said a sergeant had been sent out to tell us to retire but failed the order. He was later court-martialled and received three years for cowardice.

After ten days in the line, we went back for our well-earned ten days. Back again on duty, still around Fricourt Farm, we drove the Germans back and took over their positions. As we approached one of their dugouts, we saw a smoke curling from it, we rushed it but found it empty. It was a good comfortable one, with table and chairs and a fire burning. We thought it was “the goods.” I said to the boys, “We’ll keep this one”, and we stayed there about half an hour. Not long after that some officers arrived and took it over, telling us to get back out in the trenches. They were muddy and cold after the warm dry dugout and I remember having a little mumble to myself at the time. Less than another half hour later, the Germans opened up with artillery fire and killed all the officers in that same dugout. It was another time when I had one of those lucky breaks. The mud and the cold proved to be the best place for us after all.

We advanced again and took over an outpost held by the Germans and found it full of mud, we had to jump into it for cover and stood up all night, mud to the knees. Next day some of the boys dug a seat in the side of the outpost to sit down, but I stayed on guard on the Lewis Gun day and night for four days and never sat down once. It snowed and rained most of the time, but only light snow. At two o’clock in the morning, on the fourth day, we were relieved by another battalion and taken back into close supports, given one blanket each and a sheet of canvas (just enough to cover six men). As I had lost one man, we now numbered five, including myself. We laid the canvas onto the snow and got into it and wrapped a blanket around ourselves. My feet and legs felt dead. I had absolutely no feeling in them as I walked I had no feeling of them touching the ground. I stumbled, more than I walked.

At sun-up we were awakened to be taken back to where we could rest. By this time the snow had melted and seeped through the canvas and we were laying in pools of water. It was so cold and we were taken back to where there was a small village and told to make ourselves comfortable and dry our clothing. The sun struggled out enough to dry the blankets but it was still cold.

My feet and legs were still numb, and I had trouble trying to stand on them. I asked the other boys that could walk, to go out and see if they could find enough boards among the brick rubble to floor our dugout, while I dug a hole in the bank to give us a place to lie down. That evening when we had everything dry and made comfortable again and were looking forward to a well-earned rest and a good night’s sleep, disaster struck. At “Stand To” that same evening (5.00 p.m.) the Germans attacked the 4th battalion on our left and we went back up into the front line and were again in a muddy trench for another four days and nights. This time it didn’t snow or rain, but very little sun came out during that period. At the end of the fourth day, again we were taken back for a rest. This time we were taken to a woods, some few miles behind the front line, where they had pitched tent flys in the bush under cover. We were given a blanket each and told to get some rest. It was that night that I removed my boots from my feet for the first time in eight days and nights. The next day my feet were so swollen and painful that I could not get my boots on or even touch my feet. I couldn’t stand and could not even think about walking, so I crawled on to sick parade. The doctor told me to put my boots back on, which was impossible and I told him so in no uncertain terms, so then he marked me light duties. I told him that if he did not send me to the hospital that I would sit down there until he did. He then marked me hospital.

The battalion formed up and marched away, leaving me sitting where the doctor had seen me. I could not walk and I had no idea where I was as we had arrived there during the night. When I saw that I was being left behind, I got to my hands and knees and crawled the way the battalion went. They were soon out of sight. I crawled for what I would approximate as a mile, then I came to a road. There I found a heap of empty sand bags by the roadside, but by that time I had the knees out of my trousers and the skin off both hands and knees from crawling, so I tied my feet up in sandbags and with the aid of a couple of hefty sticks for supports, attempted to walk when an ambulance came along the road behind me, picked me up and took me to the hospital.

From there I was sent to England to hospital. This time I was sent to Bethnall Green, in London. I had trench feet. I was bad enough, but I could have been worse. I saw others in the same ward as myself that were a lot worse than me. When the nurses were dressing some of their feet they found that their toes had dropped off. They never lived, of course. I wasn’t that bad, but I did suffer severe pain.

Three months later I returned again to France and rejoined my battalion. I went back into the Lewis Gunners, but as No. 2 on the gun. A boy by the name of Wetherhead was the No. 1 on the gun. He didn't like it and so he said to me “You take No. 1 and I will go No. 2.” So I was No. 1 again on the Lewis. No one ever had to carry a rifle, but had to carry the big Lewis gun, with only a revolver (A.45) in a holster on the hip.

My platoon officer, a Lieutenant Clarke, was a fine fellow. He was a solicitor in peacetime, but he would lose his bearings in “No man’s land” at night and so relied on me many times for direction. In and out of shell holes was out of his line. Once again we were back in the front line on the Somme. The weather was on the improve. We had little or no trenches and it was mostly outpost duty. As the weeks and months went by, we took our turn in the front line, the usual ten days in the line and ten days out for a rest.

Night after night we raided the German lines and advanced steadily, driving the Germans back. The lives of many of our men were lost during this time. As a rule you didn’t get to know the men who were with you very long, today here, tomorrow killed in action. I remember one boy; he joined us just before we went into the front line. He was in my team and did not get as far as the front line when hit badly in the arm. It was his right arm, and as I dressed it for him he started to cry. I asked him what he was crying for and he said “I have only just got here and have seen nothing yet and now I’ve been hit.” I said to him “You have seen all you want to see, think yourself lucky, I would give you a fiver for that “blighty” if it were possible.” (A “blighty” was a wound bad enough to send you back to a hospital in England). I didn’t see that boy again, and never found out if he ever got out of the front line alive. These events were happening all the time but I seemed to have a charmed life. I will tell you about one small incident, just to explain how I seemed always to just miss out being killed, and how lucky I was.

One day, my gun team was up in the front line and our outpost, about thirteen yards away from a German plane that had been shot down some time before we had arrived at the front line. “Darkey”, my No. 2 said to me “1 would like to go over and see if I could get a souvenir from that plane.” I said in answer to him “well, why don’t you go?” It was broad daylight and in full view of the German outposts so he said to me “You go.” I laughed and said “I’m game if you are”, and although we knew that the Germans were watching, he answered me with “come on then.” We both jumped out of our outpost, which was about shoulder deep, and ran to the plane. We made it and jumped into a large shell hole under it as the Germans traversed the top of that shell hole, time and time again. We had to lay low there for an hour or so and then, when we thought it safe enough, made a dive back to our outpost again. The German machine gun bullets ripped the dirt along the top of our outpost. How lucky we were. Darkey said to me “Give me the gun”, and lifted his head above the ground then fired. He could not have been on target, because they returned his fire while his gun was still firing. Some of their bullets hit the gun. He said “Damn that” and I said “Give me the gun”, so I waited for their gun to stop firing, then opened up on them. I had their outpost marked and as the gun ceased to fire again, I guessed that I must have hit the gunner. After all that trouble to try to get a piece of their plane for Darkey, we found that there wasn’t anything left to souvenir. I guess that many others before us had had the same ideas.

I remember one place at the Somme, (it was referred to as the Somme, but was actually the Somme River), in a communication trench, a dead man’s hand and arm were projecting from the earth about a foot. Those boys who had dug the trench, rather than cut the limb from the buried body, left it there and many times I have seen men catch hold of that hand as they passed along the trench and say “How are you Dig?”

I had one twelve months stretch in France without leaving my unit, then I was granted fourteen days leave in England. Returning after my leave, my battalion went into the line at Hill 60 another “Hell Hole.” Hill 60 is where the British undermined the Germans. It was there that the whole German front line of trenches were blown up, in the early days of the war. I do not know the width or length but guess the length to be about a mile or more. I never did see the ends, but the depth would be about sixteen feet and the width about fifty yards. Half moon dugouts were made in the bank of this large valley, that would hold up to three hundred men in each of them. In these dugouts you could go to sleep and feel safe there. These were our close supports. Mostly it was outpost war here. My outpost was only about twenty inches deep and we had to lay down in it to keep under cover in the daytime.

My platoon officer visited the outposts at night and on his first round it was always hard to find all the outposts in the dark. It was one morning around about 1.00 a.m. when he arrived at my outpost. He flopped down beside me in the mud and said “I’m buggered.” He went on to say “I have been trying to get here since dark and it has taken me all this time from my pill box to here, I don’t think I can find my way back again before daylight, so I think you had better come back with me.” I said to him “Can’t you find your way back there?” “Not before daylight” he said. I laughed and said “How in the heck can I take you back there when I have never been there?” He said “I’ll show you where it is from here”.

The battlefield was full of shell holes and they were all full of water and limbs of trees, that had been blown down by shellfire. “My pill box is at the base of that tree” he said, pointing out a limb on a tree on the skyline. I was always good at night and was always chosen to lead the company in and out of the line for that reason. Off we went. I had only a .45 revolver on my hip so armed myself with three or four mills bombs in each pocket and had him safely back in his pill box in good time.

He said to me “There is a container of stew here to go back to the boys”, and so I slipped the container of stew onto my back and off I went on my way back. These containers had two straps fitted to slip over your shoulders and fit across the back. These are what the cooks used to send the food up the line at night. They kept the stew hot for hours. The snow was about three inches deep; this helped to see at night. I was in “No Man’s Land” and on my own, when I saw someone coming. I dropped to my knees, slipped the stew from my back, pulled out a bomb, pulled the pin out and held the lever down, then waited until they came within thirty feet and then called for them to halt. They did so, gave the password and came up to me. It was a party of twelve men looking for Headquarters. I told them that they were going the wrong way and suggested they come back with me. I slipped on the stew again and they fell in behind me and we set off. We hadn’t gone far when I saw someone else coming towards us. I waved for them to get down, and again took the stew from my back, and went through the same procedure with the bomb again. This time it turned out to be only one man, so I halted him. He in turn gave the password and it turned out to be one of our sergeants and we knew each other. He said to me “Where are you going?” “Back to our outpost”, I said. He said to me “You are going the wrong way, you are walking straight into the German lines.” “No I am not”, I said “but you are.” “You come with me” he said, but I said “If you think you are going to our line and I am going to the German line, well, you go on and I will go my way.” “I make it an order, you come with me”, he said. “Make it what you like, I’m not going with you”, I said. “Well, you’re under arrest”, he said. “Alright, but I am still not going with you.” It is a serious thing to disobey an order in the face of the enemy, but I did it knowing I was right and he was wrong, besides, I had the lives of twelve other men to think about. In spite of his order, I took the men and the stew and went on. It worried me that night and the next day. That sergeant had taken several men out on patrol with him that night, and when he approached me, I knew then that he was lost out there in “No Man’s Land.” When the officer came on his rounds the next night I reported the matter to him at once and he said “You did the right thing as he was taken prisoner up in the 2nd battalion lines last night.” Luck was in with me again.

We finished our ten days in the line and then went out for our rest again. When it was time to go back into the lines again our company commander lined us up and told us that they were expecting the Hindenberg push and that if it came while we were in the line our Artillery was going to open up a bombardment fifty yards behind our Front line and one fifty yards in front of the line, this meant sacrificing all the lives of those in the front line to stop the Germans from breaking through. I said to my mate that I would go into the line, but if I was unlucky enough to be in the line when the “push” came and if I came out alive, that it would be the end of soldiering for me, and I meant it too.

As luck would have it, I was not in the line when the “push” came. It did not come when they expected it to either.

It was at Hill 60, during 1918, in the front line that we were shelled heavily for days and nights without respite. A great many of these shells were gas shells and small gas proof dugouts had been built. These dugouts would be safe enough from small shells, such as gas shells or wiz-bangs but we had to keep our gas helmets on all the time. One night the battalion was short of men, the sergeant had warned me that all men had to be called out on fatigue except myself, as I was No. 1 on the gun. No. 1 never leaves his gun. Our shallow trench was so heavily shelled that night that the sergeant could not get to us. We waited until 10.00 a.m. and no one came to us to get the men. We were all dead tired, sleepy and hungry. We seldom, if ever, had anything to eat until midnight each night as only one meal could reach us in every twenty-four hours in the front line. At midnight that night, when the shells got lighter and rations could be brought up to us, we received a small loaf of bread, half a tin of jam and a big block of cheese between the six of us. That was to last us for twenty-four hours. We settled down when things got quiet and I put a waterproof sheet up in the little doorway to stop any gas from getting through if they should start to shell again and we all soon fell asleep. When next I awoke, it was morning. The gas had come while we were asleep and me being the closest to the door, got most of the gas. My voice was gone, except for a whisper.

You might well ask how could anyone sleep under such conditions, but if you are tired and sleepy enough, you will learn to sleep through anything, even the greatest of bombardments and not wake up. I know this to be a fact as I have done it. I did not see a doctor for five to six days after that until we came out into close supports. When I did see one, he put me on light duties, but I stayed on my gun, as usual. I had trouble trying to make the sergeant understand that I wanted to stay on the gun instead of the suggested light duties. We were all sleeping in the half moon dugout that I have spoken of in Hill 60, and a guard was always placed on duty at the mouth of the dugout in case of gas coming over. This night after the Q.M. had sent some rum up the lines for the boys, the guard on duty found it and got himself blind drunk. When the gas did come over, he was too drunk to know and the entire three hundred of us troops were gassed. This was my second dose and now I had no voice whatsoever. Our W.O. told me to report on sick parade. The doctor I had seen a few days before had been shelled in his dugout and had now been replaced by another M.O.

I went on sick parade before this new M.O. who said to me “How long have you been like this?” I raised up eight fingers as it was the only way I could tell him that I had been eight days like that. He said “Get on that stretcher, if you exhaust yourself the least bit, you will drop dead.” I did just what he told me to do, though unwillingly, and two stretcher-bearers carried me out of the trenches, along duckboards and over the battlefield. The mud was so deep, if you stepped off the duckboards you would go down over your knees. The shelling was so heavy that some of them were only missing us by a few feet. This mud was the only thing that saved us, for when a shell hit the mud it would blast straight up instead of the normal explosion. The reason for this was that the mud was so deep and the shell would go down into it. I was taken to a road and a large shell and gas proof dugout. It must have held a least a hundred stretchers and as I was the last one in and close by the door, I was also the first out when the ambulance came.

Once again I was taken to hospital in England, this time to Birmingham Hospital. I was unable to speak a word for six weeks and had to be given shock treatment from batteries placed on my chest and throat to try to bring my voice back again.

I had been in hospital for three months and was boarded for home, but the doctors said if I came back to a hot climate I would die, so I was kept in England. I was burnt black with mustard gas, and my lungs were blistered, but with time I slowly recovered. Again I found myself in a training camp in England.

Meantime, my brother Edgar, who had been wounded again, was in hospital at Newport, Wales. He had somehow gotten himself transferred to a unit, Australian Ordinance Workshops; he had been in “C” company, 34th battalion before this. He told me that they needed tradesmen and I made an application for a position with them as a wheelwright. The O.C. of the unit made a claim for me and I was sent to London for a trade test. I passed the test and went back to France in the new unit. This time I did not have to do any fighting, although we did do our work under long range shell fire and air raids but the shell fire was mostly at night.

Now we saw more of the French people and got to know them. Edgar, my older brother and I billeted with a French family, Mr. and Madam Defour and their young daughter Louise. Mr. Defour was the station master there in Bohain, a small town in France. Most of the houses had a cellar underneath and the Defour family slept down there for safety, in case of shellfire. Edgar and I shared a front bedroom of their home. One night a gas shell missed the top of our house and the house next door was hit by it. It went through the roof and landed down in the cellar of the house next door, which was occupied by three young girls, two were killed and one escaped but she was badly gassed. Madam Defour came up from the cellar and knocked on our door and kept repeating the same thing over and over in her own language, which meant “Come quickly.” She had made a bed up in the cellar with her family for both Edgar and myself and would not leave us up in the bedroom when the house next door had suffered such an attack. We went down only to please her as we both knew that if a gas shell hit the cellar we wouldn’t stand much chance. We were to spend many hours in that same cellar with the family and the next morning after the attack on the house next door the one girl that had survived the attack came into our house crying as her voice had been rendered to a slight whisper. She eventually calmed down when I told her the story about my own experience with the gas and that I was better as she would be with rest.

I was back in France for three months when the long awaited Hindenberg Push came. It was long overdue, but as luck would have it I wasn’t with my old 1st battalion although a lot of my old mates were. So, as far as I knew, they were all killed and I feel sure that the original plan was followed. It was our company commander that had lined us up and told us what to expect when and if the Hindenberg Push came. So I felt sure it was our own artillery that had bombarded their trenches to stop the Germans from breaking through. That was the last battle of the Great War of 1914-1918.

It was only ten years ago that I made a journey to Canberra and went through the War Museum. I looked up the records of my old 1st battalion and the list of killed in action and found the names of all my old mates listed there. They had all been killed in action in the Hindenberg Push, at the very end of the war. Lucky for me I was not amongst them.

I did not return home to Australia until the 19th August 1919. We were kept in France by the Captain of the unit I was in. He didn’t want to come home and so he kept us working in the workshops under some scheme of his own. When he would not break up the unit, we all went on strike and refused to work. He placed us under close arrest and charged us with mutiny. He didn’t have the power to do such a thing but he did get away with it for a few weeks, until I wrote a letter to General Monash, who was the Commander of Australian Troops in France. I wrote the General of the situation and shortly afterwards our O.C. was himself in serious trouble. I never did hear what did happen to him but we were all soon on our way home.

I was on draft for England. It was there that I met up with Harold Andrews again, of all things he was Officer in Charge of the draft. We had not seen each other for nearly a year. It was a happy reunion. We crossed the English Channel and were soon homeward bound.

Harold and I went over on the Themistocles together and as luck would have it, came back to Australia on the same ship together. We called into Capetown, South Africa, and were given leave there. We spent our time sightseeing as we took a taxi and went for a trip around the Table Mountain. The scenery was beautiful. We left Capetown that night bound for Australia but the old ship broke down and we drifted helplessly at sea for three weeks.

We arrived in Australia three weeks overdue and the ship berthed in Port Melbourne, Victoria. We had to get the train from Spencer Street Station back to Sydney. We had a wonderful reunion with our families on our arrival home. It was great to be back again after four years away at the war. My people lived at Wyoming on the Manning River, just out of the small village of Mount George at that time. I was given a welcome home in Sydney and my mother and sister Laurie and my nephew Eddie, son of my sister Ettie, rode home on the train with me to Mount George. The people of my home district of Mount George gave me a welcome home and presented me with a gold medal.

My friend Harold Andrews, invited me to meet his family and have a holiday with them. Whilst still on leave, I travelled across to Wauchope and met his mother, father and his six sisters and one brother. A beautiful family, I was made very welcome there by them and we are still the best of friends.

The people of Long Flat and the Forbes River also gave me a wonderful welcome home and I was presented with yet another gold medal there at Long Flat. Alf Way, Norm Way's brother, came over from Beechwood to Long Flat to my welcome home. He was so much like Norm that he gave me quite a shock when he sat down beside me and spoke. At first I thought it was Norm, they were so alike, but I knew that Norm had been killed in action near the end of the war.

At this time Bill Marshall had the Hotel at Long Flat. My sister, Amy, and her husband, Bob Cox, had the General Store. Peter Healy had the blacksmith shop there at that time and he asked me to go halves with him in the business. He was the blacksmith and I would do the wheelwright and coach building. I worked there with him for some time and we both boarded at the hotel. Jack Parry drove the four horses and van for Bob Cox, but Jack would get on the drink and I would take over his job and drive the four-in-hand for Bob until Jack was over his spree and could drive again.

I left Long Flat and went to Sydney. At the time Clyde Engineering was calling for carriage builders. They had just taken a contract to build fifty new electric railway carriages. They were the first electric carriages to be built in New South Wales. That was early in 1921. I was married in the same year, on the 7th May, 1921. That was while I was working at Clyde on the electric railway carriages. It was not long after the war and my nerves were still not back to normal. One day, not long after I started to work at Clyde, while I was working at my bench by the side of a carriage, some men came along to do some rivetting under the same carriage. I didn’t notice them at the time and I had never seen or heard an electric rivetter operate before, when it opened up it was just the same sound as a machine gun. Without a thought, I threw myself face down on the floor, every one laughed at me, but I didn’t see the joke. If they had gone through the terrible experiences I had gone through in the past four years, they would have done the same thing. It took me years to get over the shock of war. When being shelled the only chance you have of saving your life is to get down quickly. I have thrown myself in the lower side of a brick cobbled street, not much more than five feet from where a German shell hit the roadway and didn’t even get a scratch, where others who didn’t react quickly enough were cut to pieces from the flying pieces of shells.

I worked there on the electric railway carriages for a year. It was while I was still there that I became ill with appendicitis and before I could be taken to hospital, the appendix burst. I was extremely ill in hospital for a month. When leaving the hospital, I had to have assistance to walk.

It was another five weeks before I was able to resume work and was forced back earlier than I should have been by lack of funds. I only stayed at work there for another three weeks and then had to give the job away. I left Sydney and went back to Wyoming on the Manning River and stayed with my mother and father for three months until I was well and strong again.

From there I went back to Long Flat and took a job driving a T. Model Ford truck carting cream from up the river to Wauchope butter factory.

At this time, Peter Healy from Old Bar, a beach resort near Taree, had married my sister Laurie and was living on the Comboyne and had the blacksmiths shop there in the village. I went to work with him again for a while and then went to Wauchope and did some work there for Dan White the blacksmith. I made the wheels for him that he put on the sulky that took off the first prize at Wauchope Show.

Herman Everingham was then the agent for Albion trucks. I went to Newcastle with Herman to bring the truck home. I drove the truck for twelve months and then became ill.

Dr. Begg from Wauchope said I had Bright’s Disease and put me in Wauchope Private Hospital. From there I went to Taree to see Dr. Stokes, who said that I didn’t have Bright’s Disease, but a sister complaint. He put me into Taree Hospital where I spent the next eight months.

From Taree I went to Randwick Repatriation Hospital in Sydney and stayed there for another four months. It was while I was there that the Defence Department ran an advertisement in the paper for a wheelwright. I made an application for the job and was successful. When I came out of Randwick Hospital, I went to Liverpool and took over the job and was the Wheelwright there for twenty-five years.