This quilt was made during the Malay Emergency. This was a continuation of civil unrest after WW2 and also during the Indonesian Uprising when Australia defended Malaya against an Indonesian landing.

My mother Rosemary sewed her quilt alongside army wives from New Zealand, England, Scotland and Nepal. They would sew, smock or knit while the kids happily ran wild. This was at the beach club, a paradise for these expats, with its jungle backdrop of beach and pools in Terandak British army camp, near Melaka (Malacca) in Malaya in 1964-65.

These army wives and children would come down every afternoon after school. The men were generally not there so, to distract themselves during the weeks and months of separation, the women would seek each other’s company and do something practical.

When the men did come down it was often a relief for them to dive into the water, according to my mother, because they were also managing to control the civil war of the Malaysian Races Liberation Army. This was made up largely of ethnic Chinese Communists who opposed the creation of the Federation of Malaya as they believed it did not directly lead to the creation of a Communist State, and who of course hated the English.

The husbands had to learn guerrilla-type warfare. Sometimes we weren’t allowed to leave the camp because of unrest or disease outbreaks like cholera. It was quite normal for dad to be missing at breakfast, having gone off in the night. Into the jungle with the big leeches. Sometimes to Borneo for months. Even to Vietnam.

The quilt was made for me, (it has blue corners, my sister was always given ‘pink’). Apart from the memories of pyjamas and dresses in the patches, there is also a number of local batik pieces, friends’ evening dresses and fabrics from Africa and Japan. Patches with rockets commemorate Explorer, Atlas and other NASA voyages – and it was my birth year, 1958.

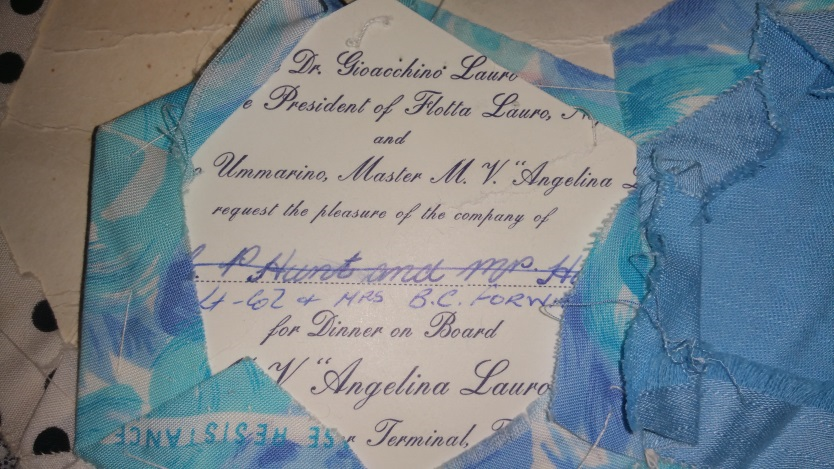

The backing cards (cardboard that hold the fabric in place) are also of interest historically. Hexagon reshaped Christmas cards, and a printed invitation, to the 1st Battalion NZ Infantry Christmas party. Tradition has kept the quilt together. A dinner invitation from my parents’ friends – black tie and that was to his birthday party! And the ladies would regularly send gilt edged cards to their friends with ‘at home’.

There used to be night parades in camp. I was enraptured by the glowing eyes of the Scots Guard big bass drummer’s leopard skin apron as he passed. (I learnt Scottish dancing at classes after school.)

I suppose memory is the media of the mind. The happiness and suffering that dissolve into it. How you interpret what you see, hear and feel is true for you. If I’d had a camera, I would have photographed the baby catfish I’d captured while playing where a forest stream met the sea, or, the now rare, prehistoric horse shoe crabs with their long tail like venomous spines and, of course, the pirates’ grave site. On Sundays when families would go to the Officers’ mess, I was yet again able to roam freely. A little gang of us bravely scouted a trail to a strange largish, rectangular building. It had only three medium height walls, a doorway with no door. A tiled roof supported by upright beams from the walls meant it was open to the elements. A dirt floor with nothing more than 2 small holes in it led to a sheer vertical drop and a magnificent view of the Melaka Strait. This was a pirate grave, for the two unnamed pirates and the holes for them to come out and eat the food the Malays would leave for them on newspaper on the walls. What a great site for these men’s spirits! It showed their importance because here they would eternally watch. It was an important lesson to a young person about death and the afterlife.

I returned to Terandak and Melaka when I was 19 as a backpacker. I took a stroll in the cemetery of earlier Batavian colonists. I have a photo of a headstone, “to the memory of Captain John Kidd.” I assumed that his body had been removed to be reburied, just as they had done to St Francis Xavier from up the hill. (His uncorrupted body was moved from Melaka to Goa nine months after its temporary burial in St. Paul’s Church in 1553.) Mr Google now tells me that John Kidd was father of the infamous pirate William Kidd who was born in 1701 in Scotland. His family had been left in poverty as John Kidd had been ‘lost at sea’. Well someone remembered the older pirate and had made a large gravestone, and William continued the family tradition. As do the current Melakan pirates.

The story continues to Perth and Queenscliff in Victoria. By this stage mum was doing the last patches. There is one card with a very poignant story.

On an invitation to go on board the Angelina at the passenger terminal in Fremantle, 17th April 1966, the names of the invited guests Brigadier G Hunt and Mrs Hunt have been crossed out and Major and Mrs Brien Forward has been written by hand underneath. Not etiquette. Upon asking my mother, she replied that it must have been when the Brigadier became sick, and that frequently people would go in his place to functions. Even stranger. Dad had been warned that his new boss, Brigadier Hunt, was difficult and uncommunicative. He had been a POW in Malaya in WW2. So dad thought he’d just work hard and do his job. Dad generally went along with Hunt’s demands but would occasionally help him modify his orders. Hunt was victim of the imbecilic understanding that a stiff upper lip would solve your war damage. My father had experienced loss first hand when his best friend was killed in Korea. Dad had replaced him as reconnaissance pilot over North Korea. He had known good men who had become POWs. He was familiar with the effects that intense suffering could have on people and he had left Korea with a marked eye twitch which resolved itself with time. He had enlisted at 15 and would have been there when he was 23.

Brigadier Hunt in Singapore had experienced a loss of faith in his superiors. As camaraderie is one of the quintessential facts in warfare, the controversial abandonment of the soldiers in Singapore by their Commander General Alan Bennett, left a deep scar on many. In 1970 my father also had a similar thing happen when the then Minister for Defence, Killen, denounced NZ troops in Parliament. Attached to 4 Field Regiment their Australian officer in charge had ordered them to practise with live ammunition rather than blanks in a supposedly unpatrolled area in Vietnam, resulting in the deaths of many US soldiers. As the Regiment’s Commanding Officer dad wrote to the Governor General, the PM and opposition PM, the Minister of Defence and the major newspapers stating the truth, that it wasn’t the Kiwis’ fault. An emergency meeting was held in Canberra, to decide if he would be court martialled. He wasn’t. This all happened on the day I had won tickets to Luna Park. Mum, having to take my sister and me, was rather distracted reading about dad all over the front page of the Australian. At 12 and 10 we weren’t very interested. The amount of public support he received was staggering. I know this because I heard mum argue with him, a few years later, when he threw away all these letters. He had started to suffer from the same disease as the man whose name, and his wife’s, had been crossed out on a gilt edged dinner invitation.

The military is a sort of life I learnt to love as a child, it was safe and exciting. Very difficult with schooling but that ‘toughened you up’. As an adult you see through the parades and ‘gongs’ on their chests, the ads for battleships at Canberra Airport by lucrative armament companies, and the fired up language of attack that has crept into our daily vocabulary. The Law of Armed Combat is now perhaps a game of words that justifies how a government didn’t really go beyond what was humane or civilized.

My family was scarred when my father died at 46 but I continued to believe that our un-uniformed politicians made ethical and honest decisions to benefit us and our allies. Now I know why my father detested ‘gunrunners’ munitions sellers who never joined the fighting or paid reparations. He fought to save lives and people, and families in Vietnam. He became disillusioned when he realised that they had been placed in another country’s civil war. The politicians knew in 1963 that the South Vietnamese as allies had few strengths to be able work alongside skilled professional armies. And the Officer who informed them, was court martialled. Only to be employed as an expert contractor later.

I love yet I hate what an armed force can do. In fact, I know that continual Peace Making is the ultimate solution.

The camaraderie of my father’s Duntroon class of ‘48 lingers on. At a recent wake of one, I could hear the whisper “that’s Brien Forward’s daughter” as I passed. I joined them. They respect me because they respected or loved him. Ken Hill, one of these diggers who loaned me books and discussed events with me as I was writing this, recalled a telling story. His brother, an Airforce officer, had worked excessive hours alongside my father at Russell HQ in 1975 in Canberra. “Giving our life blood,” dad would mutter at home, to over-demanding generals and politicians. Air commodore Vin Hill AFC DFC and bar, on learning that Dad’s stress provoked a fatal heart attack, decided to resign. And did so immediately. Another sort of camaraderie.

Back to the quilt… George Hunt was artillery, a gunner, like dad. He would talk at length with dad, when he hadn’t been able to talk to anyone else. He had become remote and a stickler for formality, ‘a lost soul’ according to mum. People would talk to him but he wouldn’t reply. Not really acceptable for a Brigadier and not really good at parties. It got to the point where it took time away from dad’s work by his becoming Hunt’s confidante. Hunt needed to talk. He’d needed to do so for the last twenty years. Dad applied to do his superior’s official history but the reply was ‘put to one side’. Hunt was discharged in November 1966 while we were getting ready for dad’s next posting to Staff College in Queenscliff. He was 54. He’d enlisted in 1940 at age 28.

There’s another interesting backing card. An emblem of an owl with a crown standing on two swords and the motto “Tam Marte Quam Minerva – As much by the pen as the sword.” The Roman goddess of wisdom Minerva carried an owl and the swords were of Ares, the Greek god of war. As Pakistan, from where this card came, has the Appian Way run through it and has Roman and Greek culture in its history, it’s not a surprising combination of Rome and Greece. This had been the motto of the Pakistani British Commonwealth Staff College but it was changed in 1950, to the 13th Century Persian poet Saadi saying, “Pir Sho Beyamoz, – Grow Old Learning.” In 1956 Pakistan became a Republic and the crown was removed. But somehow an old insignia travelled to the Queenscliff Staff College in 1968 with students from Quetta Pakistan, and made it into the quilt!

A posting to Townsville and 2 house moves in the one year didn’t leave any time for mum to sew. The focus was on preparing 4 Field Regiment for Vietnam and I think mum was very worried. She had every right, as dad returned a changed man – the facial tick also returned.

The quilt is hand stitched with very small stitches. It has been finished thanks to the kindness of another group of women who came to a working bee at the Boab cottage in Queanbeyan NSW. Some had war stories but they all had peace stories and we laughed.